Our Insights

Through writing, analysis, and our insights, Bellwether’s got the pulse on what’s happening and emergent trends in the field.

Featured Insights

Splitting the Bill: A Q&A on School Funding for English Learners with New America’s Leslie Villegas

Celebrating Leaders in Education: A Women’s History Month Q&A

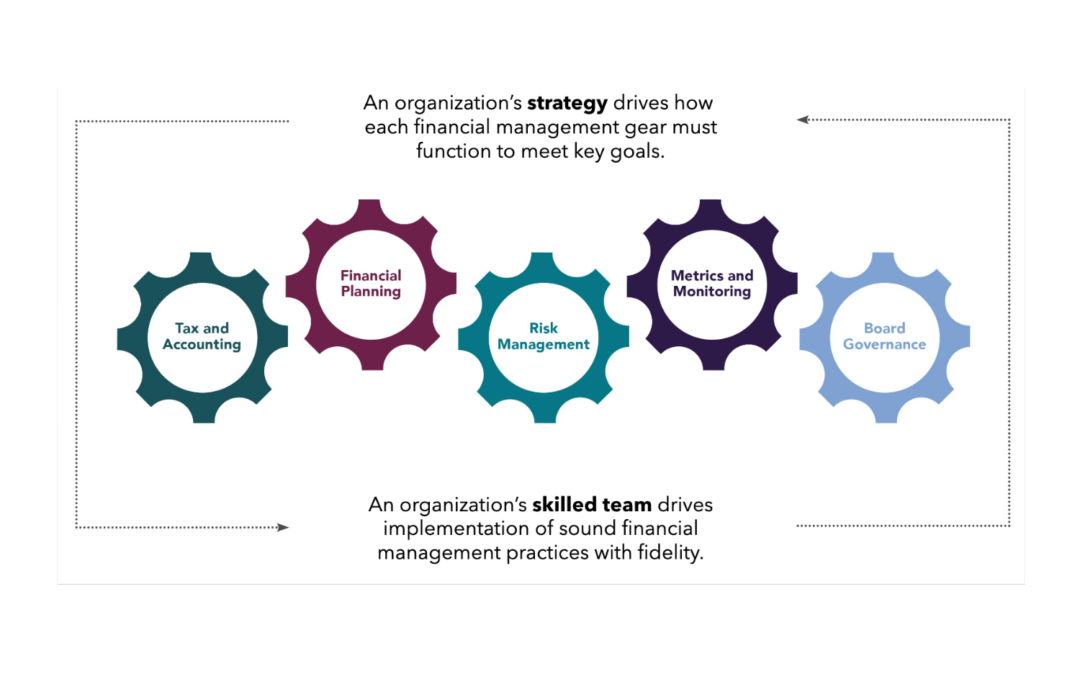

A Sustainable Nonprofit Starts With Effective Financial Management

Splitting the Bill: A Q&A on School Facilities Funding with Public Policy Institute of California’s Dr. Julien Lafortune

Publications

Dollars and Degrees: A Bellwether Series on Higher Education Finance Equity

Strengthening State Higher Education Funding: Lessons Learned From K-12

Splitting the Bill: A Bellwether Series on Education Finance Equity

After the Policy Win: First-Year Implementation of Tennessee’s New School Funding Formula

Blog

Splitting the Bill: A Q&A on School Funding for English Learners with New America’s Leslie Villegas

Celebrating Leaders in Education: A Women’s History Month Q&A

A Sustainable Nonprofit Starts With Effective Financial Management

Splitting the Bill: A Q&A on School Facilities Funding with Public Policy Institute of California’s Dr. Julien Lafortune

News & Press

Seven Assembly Grant Program Grantees Will Increase Families’ Access to Flexible, Personalized Learning

Request for Qualifications: Academic Strategist Services

Annual Report 2023

Assembly Grant Program

All Insights

Filter Insights

Sort

- Date